We were recently asked by Huffington Post to comment on philosopher Daniel Dennett’s TED talk. Our response can be found here — or below.

Time to put humor under the microscope

Daniel Dennett makes a good point in his TED talk, Cute, Sexy, Sweet, Funny, when he argues our sense of humor must accomplish important evolutionary objectives. Why else would we find things funny and laugh about them – pretty unusual activities, when you think about it – unless doing so helped us survive as a species?

According to Dennett, humor evolved as a way for the mind to incentivize the discovery of mistaken leaps to conclusion – or as he puts in his talk, it’s “A neural system wired up to reward the brain for doing a grubby clerical job.” This so-called “Hurley model” (named after lead author Matthew Hurley), makes sense from an evolutionary perspective.

But the Hurley model of humor is based solely on argumentation, intuition and thought experiments. To be sure, that’s been the de facto way of devising humor theories ever since Plato and Aristotle contemplated the meaning of comedy. But the results don’t always withstand scientific scrutiny. Take incongruity theories of humor, which are based on the intuitively-appealing belief that humor arises when people discover there’s an inconsistency between what they expect to happen and what actually happens. In truth, scientists have found that in comedy, unexpectedness is overrated. In 1974, two University of Tennessee professors had undergraduates listen to a variety of Bill Cosby and Phyllis Diller routines. Before each punch line, the researchers stopped the tape and asked the students to predict what came next. Then another group of students was asked to rate the funniness of each of the comedians’ jokes. Comparing the results, the professors found the predictable punch lines (i.e., the less incongruous ones) were rated considerably funnier than those that were unexpected.

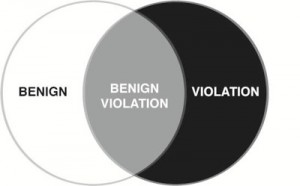

That’s why when Pete, the scholarly half of our duo, began wondering what makes things funny, he launched the Humor Research Lab, aka HuRL. With his collaborator Caleb Warren, he’s been developing and testing the benign violation theory, the idea that humor arises when something that is unsettling, threatening or wrong (i.e., a violation) simultaneously seems acceptable, safe or okay (i.e., benign). All kinds of humor fit the model, from puns to sarcasm to tickling. But more importantly, the theory is being validated experimentally.

In one HuRL experiment, a researcher approached undergraduates and asked them to read a scenario inspired by Rolling Stones guitarist Keith Richards. In the story, Keith’s father tells his son to do whatever he wished with his cremated remains—so when his father passed away, Keith snorts the ashes. Those who found the tale of Keith and his obscene schnozzle simultaneously “wrong” (a violation) and “not wrong” (benign) were three times more likely to smile or laugh than either those who deemed Keith’s actions either completely okay or utterly unacceptable. If appreciating humor is simply a mental debugging system, as Dennett suggests, these results are hard to account for.

Also encouraging are the results from our Humor Code project, a global expedition exploring what makes things funny. Everywhere, we found evidence that humor is born from violations, from things that are wrong, threatening or disruptive. We accompanied Patch Adams on a clown mission into the Amazon, where the jokesters helped impoverished communities by breaking down social norms and shattering cultural preconceptions. And in Palestine, we discovered a vibrant comedy scene mining the decades-long turmoil for laughs.

Similarly, it was clear from our travels that humor only takes root when situations are also playful, safe, or otherwise benign. In New York, we learned from the geniuses behind The Onion that even something as terrible as the 9/11 terrorist attacks can be joked about in a timely fashion, as long as the butt of the joke deserves it. And in Japan, we discovered that nearly anything goes in the name of hilarity, but only when it occurs in certain “safe” locales like comedy theaters, odd game shows, and of course, bars.

What’s nice about the benign violation theory is that it fits from an evolutionary perspective, too. According to influential work by evolutionary scholars Matthew Gervais and David Sloan Wilson, laughter likely first evolved between 2 and 4 million years ago as outgrowth of the breathy panting emitted by primates during play fighting. This early form of laughter was a signal that danger was low, and now was as good a time as any to explore, to play, to lay the social groundwork that would lead to civilization.

“There could be a violation or incongruity of expectation going on, but what’s being signaled by the laughter is that it’s not serious, or it’s benign,” Gervais told us. “What the humor is indexing and the laughter is signaling is, ‘this is an opportunity for learning. It signals this is a non-serious novelty, and recruits others to play and explore cognitively, emotionally and socially with the implications of this novelty.”

Do benign violations underlie all of what we have evolved to find funny? To be sure, arguments, intuitions and world-wide travels will inform the answer – but, in the end, let’s settle it in the lab.

Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, and pre-order a copy of The Humor Code, to be published by Simon & Schuster on April 1, 2014.

Beautifully written.

Hi HuRT ;]

I’ve been following The Benign Violation Theory you’ve been suggesting since I read about it in an article that appeared in The Boston Globe a few years back. I think its a wonderful theory and it definitely seems to explain a lot from a theoretical standpoint regarding what makes people laugh. But I’m not sure its really a theory about humor, though.

Please keep in mind along the way here that I’m a big fan of what you’re doing and actually have invested some time in studying some of these matters that Benign Violation Theory touches upon — so, my comments here are not meant to be impolite or mean-spirited, they’re just some informed and researched comments at best.

If I recall correctly — and please correct me if I’m off here — the theory states an almost formulaic, universal method to trigger laughter from another person. Anyone that’s read Provine’s ‘Laughter: A Scientific Investigation’ probably understands that although we often associate laughter with humor, the 2 are not as nearly tethered as might be expected.

Also, not all humor intends to make people laugh. I’m sure that a humorist like Mark Twain wouldn’t expect his readers to be totally LOLing all the way to the banks of the Mississippi, now, right? Some humor is meant to enlighten the reader, maybe bring a smile or a smirk, but mostly meant to comment on some sense of unspoken observational truth that we don’t oftentimes want to admit to in polite societal public circles.

Benign Violation Theory seems a little less of a theory to me than a really interesting and clever comedic strategy, right? It involves a little bit of shock and awe with just enough of that feeling of safety to make us folks in the audience realize that nobody’s gonna judge us if we laugh in this particular comedy club setting or in this hilarious but potentially offensive film scenario.

Another example that comes to mind, and this one’s a classic by the way, is the old laughing at the funeral issue that comes up from time to time. This is what would be labeled ‘inappropriate laughter’ — and sometimes the context in which laughter is deemed inappropriate drives up the tension knobs well-enough to make it almost impossible to avoid the laughs. But in this instance, who’s getting violated? And who’s violating? The corpse in the coffin — surely the main object inspiring the tension in the room and hence the reason one might laugh inappropriately — couldn’t possibly do something active to violate anyone at the funeral services, right? Or does the sense of death and our empathy for the deceased cause a near-enough violation to produce laughter? And in this particular scenario, is death or the presence of the deceased person humorous in any way? How do we actually judge what is humorous? Doesn’t our milage for ‘what is considered funny’ vary significantly depending upon: personal life experiences; cultural considerations; spacial and temporal context; our current mental state; chemical and alcoholic intake or influence; and the general vibe from other people in the room at the time of the supposedly humorous event?

One other ‘for instance’ that comes to mind regarding humor, comedy, laughter and funniness — not all humor needs to feel like a violation or threat to the viewing audience to actually produce laughter now, does it? I’m almost certain that a beautiful ballet performance can be purposely choreographed to produce laughter solely through movement as coordinated with rhythm and sound. I actually do not think any sense of ‘the unexpected’ needs to come up and I also do not think that the piece necessarily needs to go down in history as a notoriously ‘humorous’ movement piece.

I’m looking forward to reading The Humor Code. I still have some tidying up of my own research into these matters myself, although I veer toward experimenting with Dark Humor — which can sometimes result in laughter, sometimes not, but somehow always remains affiliated with humor.